Film & TV Writer Cassandra Fong looks back on Jesus Christ Superstar (1973), analysing its intricate and purposeful cinematography, and unconventional structure, finding it revolutionary for its time

In an age of ultra-HD, algorithmically optimised storytelling, few films from the 1970s continue to spark as much cultural and aesthetic debate as Norman Jewison’s Jesus Christ Superstar (1973). This cinematic adaptation of the landmark stage rock opera by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice remains as bold as ever—both in its themes and in its craft. More than five decades later, it stands not only as a milestone of musical cinema but also as a technically provocative film that anticipated many of the stylistic risks modern filmmakers take for granted.

While audiences today might initially approach it as a religious curiosity or counterculture relic, Jesus Christ Superstar proves itself to be a highly stylised and forward-thinking experiment in form and genre. Its relevance in 2025 lies as much in its technical audacity as in its enduring cultural critique.

Director Norman Jewison (In the Heat of the Night, Fiddler on the Roof) crafts a film that is simultaneously intimate and epic. He makes the radical decision to film the story entirely in the deserts and ruins of Israel, often using natural light and wide-angle lenses to emphasise isolation, vulnerability, and transcendence. There’s an intentional sparseness to the staging—no elaborate sets, no digital effects—yet this minimalism works in sharp contrast to the emotional and musical intensity of the story.

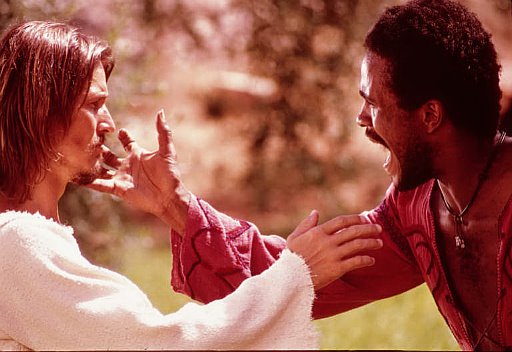

Jewison uses this stripped-back environment not to historicize the story but to deconstruct it. Actors arrive by bus, rehearse in costume, and break the fourth wall in ways that nod to Brechtian theatre, constantly reminding viewers of the artifice, and inviting them to question not just the narrative, but its place in our modern mythology.

The cinematography by Douglas Slocombe (Raiders of the Lost Ark) is both painterly and purposeful. The wide desert vistas convey scale and spiritual emptiness, while tight handheld shots during emotionally charged numbers create intimacy and immediacy. The camera movements are often fluid, tracking dancers and singers across rocky terrain without losing their energy or intention.

Slocombe frequently shoots through diffused sunlight or dust-choked air, casting halos around key figures and evoking classical iconography without relying on explicit religious symbolism. This naturalistic lighting juxtaposed with stylised costume and choreography produces a dreamlike aesthetic, blurring the line between historical past and contemporary allegory.

In today’s era of digital colour grading, the film’s earthy palette—rusts, whites, golds, and ochres—remains remarkably modern. Its tactile visual style, born of necessity and film stock limitations, now feels more authentic than many overly processed modern productions. This naturalistic lighting juxtaposed with stylized costume and choreography produces a dreamlike aesthetic, blurring the line between historical past and contemporary allegory

As a sung-through musical with no spoken dialogue, the film’s pacing is governed by rhythm and melody rather than conventional plot progression. Editor Antony Gibbs (Performance) leans into this by structuring scenes as discrete music videos—each number self-contained in its choreography and cutting rhythm, but building toward an emotional crescendo. This results in an unorthodox but hypnotic cadence that aligns with the themes of confusion, contradiction, and catharsis.

Transitions between numbers are sometimes jarring by design—cutting from celebratory dances to quiet introspection without warning—mirroring the mood swings of both the characters and the masses surrounding them. In 2025, with the dominance of TikTok editing styles and music video pacing in mainstream content, this editorial style feels unexpectedly contemporary.

Unlike today’s pristinely mastered digital musicals, Jesus Christ Superstar was recorded with analogue equipment, capturing the grit and texture of live performances. The vocals—often recorded on set or on-location—carry imperfections that only enhance the film’s raw emotional register. You can hear breath, strain, echo, and urgency in a way that modern auto-tuned productions frequently polish away.

Webber’s score blends hard rock, funk, soul, and classical elements with surprising cohesion. Carl Anderson’s searing high notes, Ted Neeley’s anguished falsettos, and Yvonne Elliman’s gentle, aching melodies all stand out not only for their performance but for their placement within a layered, theatrical soundscape. Orchestrations include distorted guitars, harpsichords, brass stabs, and gospel choirs—all mixed in a way that privileges emotional expression over fidelity.

In 2025, when many musical productions trend toward overproduction, the sonic imperfection of Superstar now feels revolutionary again. It sounds human, and therefore timeless.

More than fifty years after its release, Jesus Christ Superstar remains a technically adventurous and thematically potent film. It’s a case study in how music, image, and ideology can converge into something neither documentary nor pure fiction—but an operatic meditation on the cyclical nature of belief, fame, and human failure. In 2025, when many musical productions trend toward overproduction, the sonic imperfection of Superstar now feels revolutionary again. It sounds human, and therefore timeless.

For viewers today, especially those interested in the evolution of musical cinema or the intersection of pop and politics, the film offers more than nostalgia. It offers a mirror. Technically daring, musically fearless, and emotionally challenging, it holds up not in spite of its era-specific quirks, but because of them.

More from Redbrick Film & TV:

Hidden Gems: Lars and the Real Girl

Comments