Jen Sawitzki mourns the loss of MUJI Birmingham, and considers how its legacy has made her more aware of her behaviours as a consumer

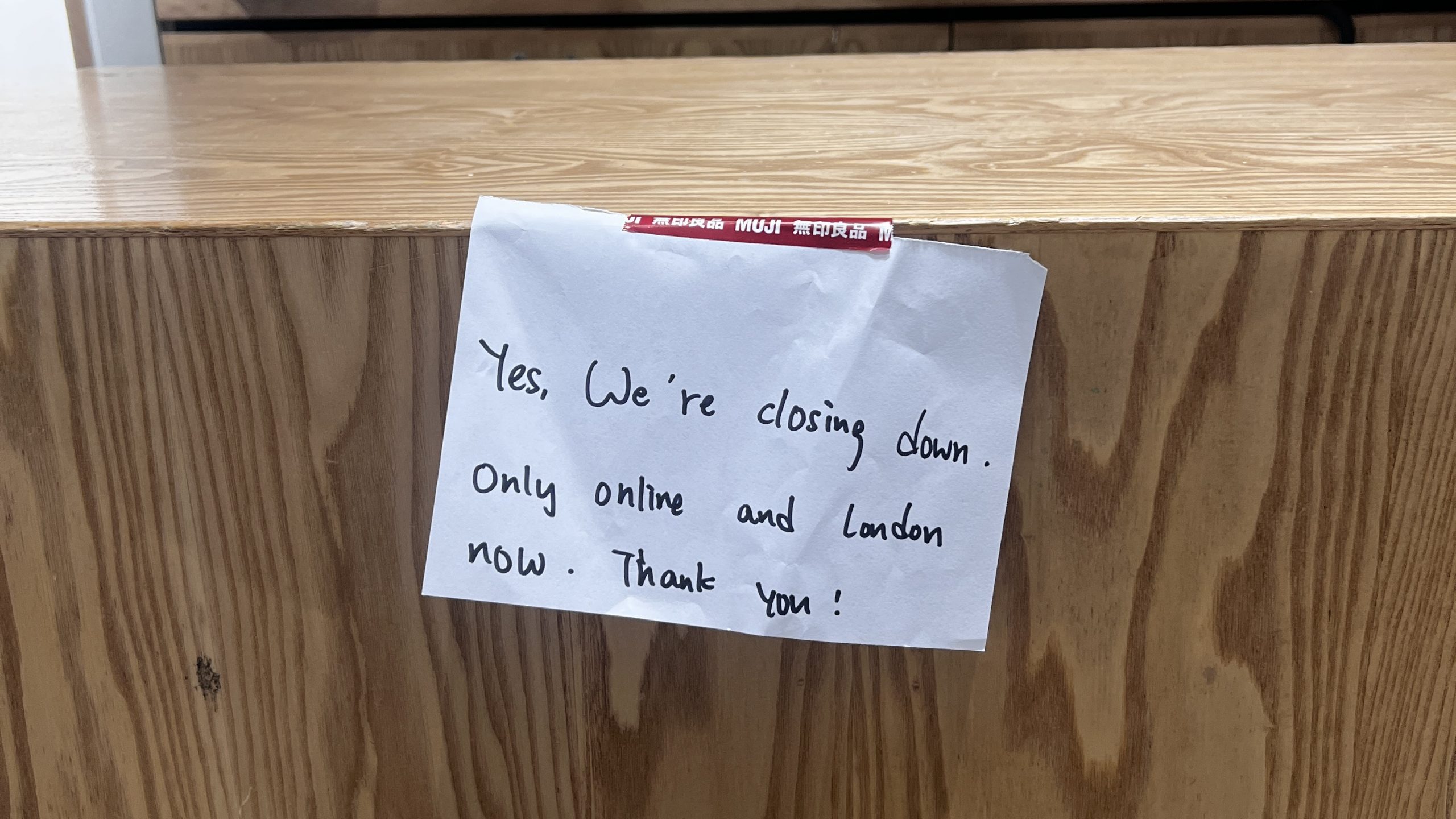

At first I was sure they were talking about another store, but after overhearing a rather downcast conversation between a stunned customer and a worker I gradually understood that it was MUJI that was closing down.When I came in circa two weeks later and spotted the ‘FOR SALE’ and ‘ONLY £3’ signs, I wanted to crawl into a ball in the changing rooms and cry for a little bit.

As someone who gets overstimulated in Primark after about 3 minutes, the beauty of MUJI (full name: Mujirushi Ryohin, or 無印良品) lies in their simple philosophy: ‘No Brand Quality Goods.’ One option for each product, all organised and laid out logically, with ambient (only slightly pirate-y) music in the background: a quiet sanctuary in comparison to all of New Street, especially Primark.

As someone who gets overstimulated in Primark after about 3 minutes […]

Being a brand that promotes the ‘rational satisfaction’ of customers (‘this will do’ mentality), as opposed to one that relies on crafting products designed to trend on TikTok, evoking a ‘Feeling of Missing Out’ (‘FOMO’), and producing a ‘I must have this product’ mentality in customers. MUJI’s advertising strategy (or lack thereof) avoids this dependence on customer’s vulnerabilities and primal behaviours – already deemed immoral by many. Often overshadowed by MUJI’s sustainability initiatives, I believe this is the main thing that differentiates it from other overly-manipulative brands.

In a world where all things reusable, ‘green’, and ‘eco-friendly’ are in price brackets, that only those who drove Minis in sixth form and gap-yeared in Southeast Asia can afford, MUJI are the exception. For the same price, you can get a cute button-down from H&M, or a 100% cotton shirt from MUJI that will last for ten times as long. This isn’t because they pay their staff or manufacturers a horrendously low amount, but because almost no money is spent on advertisements or branding. This ‘generic brand’ strategy has allowed them to produce much higher goods, compared to those manufactured and sold by other companies at the same price point.

Whilst they are famed for their minimalist packaging, the self-described ‘eco-friendly’ shop does have their fair share of greenwashing issues. I agree, as do many others, that this is an issue. In my opinion, large corporations like Ryohin Keikaku Co., Ltd will simply find another way to mislead customers in order to increase profits. I’m not perhaps as harsh on MUJI as I am other brands, but this is due to how they promote a more simple and sustainable way of living; something I believe consumers would gain much more benefit from. Removing money as a limiting factor, most people would likely own the same amount of items, only in varying quality and ‘eco-friendliness.’ As humans, we always have and always will continue to want things – new cave paintings, the most recent stone tool, the trendiest pantaloons. However, MUJI promotes the buying of undecorated goods, revealing how influenced we are by useless, nicely advertised and packaged goods. Their promotion of plain goods allows us to assess whether we need the thing or not, encouraging awareness of what we are consuming. I hope that this will result not just in long-term change, but changes to consumer habits over generations.

As humans, we always have and always will continue to want things

For me, MUJI symbolises a different philosophical approach to consumption above anything else. At the risk of sounding snobby (and parasocially obsessed with MUJI), I feel physically relieved after having simplified my life through buying less, and ‘Marie Kondo-ing’ my possessions that don’t bring me joy.

In an ideal world, this MUJI-shaped hole in my heart would be soon replaced by an English version of the company. Unfortunately, this seems unlikely. With many big brands of the 2010s (namely Debenhams, Cath Kidston, and Topshop) switching to online-only, it seems as if we should just be grateful that the remaining UK stores (all London-based) still take up physical space as opposed to an SD card. This is not a problem unique to UK highstreets, with the Japanese brand also closing all stores in Sweden, Switzerland, Indonesia and Turkey. An aptly-named article by Barbra Ellen highlighted how we are contributing to the closing of big-name stores like MUJI, alongside independent shops. ‘We shed crocodile tears over our high streets then click online and finish them off’ brings to light the democratic power we still hold when choosing whether to support Amazon (for the fifth time this week) or our local specialist provider (that we’ve been meaning to go to for the last two years).

With ‘underconsumption core’ slowly catching on and becoming trendy online, I truly hope that consumers’ mindset permanently shifts more towards that of traditional Japanese design. Focusing on ethics and high quality, over aesthetics and quantity benefits everyone – mentally, physically, and socially – as well as the added bonus of improving the health of the environment and your wallet’s. The bar remains low for companies in this modern age, but MUJI Birmingham just about got over it.

Read more from Comment:

Comments