Film Editor James Richards praises the uneven ambition of Kenneth Branagh’s genre-bending Poirot mystery A Haunting in Venice

Kenneth Branagh plays to the rafters.

t

On stage and screen alike, the Irish actor-director has consistently aimed for broad appeal. This is the man whose Henry V (1989) and Much Ado About Nothing (1993) revived cinematic Shakespeare after two decades of Polanski-induced oblivion. The man whose first two turns as detective Hercule Poirot seemed the apotheosis of an already-massive career. This lukewarmly received double bill melded the all-star theatrics of Sidney Lumet’s Murder on the Orient Express (1974) with a soul-searching angst that was once so à la mode: Branagh’s was undoubtedly a Poirot with his sights set on popular success. For this reason, A Haunting in Venice (2023) feels like an oddity: a Branagh murder mystery that sees the great orchestrator playing in an intriguingly minor key.

Branagh’s film begins. We see Poirot living in self-imposed Venetian exile. The year is 1947. The detective has stopped taking cases. His hair looks greasy and brittle. His fighting spirit has gone. He measures his morning eggs with a tiny metal gauge.

Branagh doesn’t just chew the scenery; he devours it, swallows, licks his lips, then asks for a second helping

t

The arrival of Ariadne Oliver (an underutilised Tina Fey) changes all this. Oliver, a mystery author and old friend of Poirot’s, invites the great detective to a Halloween séance at a ramshackle old palazzo. Poirot accepts, with an eye towards debunking supposed medium Joyce Reynolds (Michelle Yeoh). His zest for life has returned. His hair looks springy and virile. The stage seems set for a good old-fashioned murder mystery.

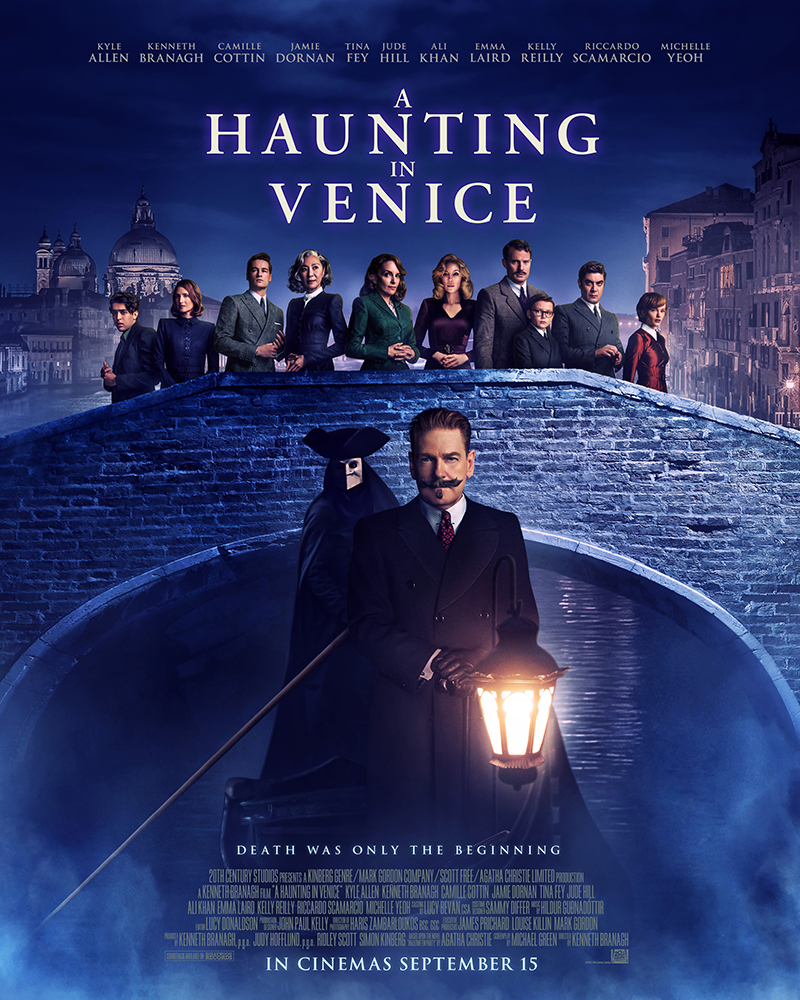

tAs the tension rises, so does Branagh. Like many before him, the actor relishes his chance to play the lavishly moustached Poirot: Branagh doesn’t just chew the scenery; he devours it, swallows, licks his lips, then asks for a second helping. Another fact has remained constant across cinematic Poirot adaptations: that the world’s greatest detective needs an equally great supporting cast. Haunting’s ensemble, while not as starry as those of its two predecessors, is nonetheless impressive. Recent Oscar winner Michelle Yeoh is an easy highlight, adding intrigue as psychic (or con woman?) Joyce Reynolds.

tWhile Branagh seems somewhat content to play to his strengths, he also leavens his detective narrative with various horror tropes. As the bodies pile up, Haunting’s isolated nocturnal setting provides fertile ground for scares. While not every moment of horror pays off (an opening dream sequence comes across needlessly spooky) Branagh’s film generally delivers on its shocks, well-aware that the über-rational Poirot is most vulnerable when his powers of deduction seem themselves suspect.

t

t

Hallowe’en Party, the 1969 Christie novel on which Haunting is based, is not the most obvious choice for a big budget feature. This late-period Christie novel seems like an odd duck compared to Murder on the Orient Express and Death on the Nile; the icons that inspired Branagh’s previous two Poirot efforts (2017 and 2022). Even David Suchet’s Poirot (which spanned twenty four years and only ended because it physically ran out of Poirot stories to adapt) took until its twelfth series to get to this particular novel.

tIn lieu of name recognition, Branagh chooses to emphasise the supernatural stylings of this original text. Much of Haunting’s tension hinges on the audience’s willingness to believe that the ghosts of the story might indeed be real – a willingness undercut by the fact that its two predecessors were decidedly not supernatural in nature. Might Haunting have therefore worked better as the very first on-screen case for Branagh’s Poirot?

Even when verging into silliness, Branagh’s film is lousy with charm and feels largely cohesive from tone to visuals to story

tThe style of the film is part and parcel of its newfound horror. Gone are the spotless CG vistas of Death on the Nile; Haunting (for the most part) feels analogue and lived-in. Branagh’s off-kilter direction, rife with uncanny fish-eye lenses and disorienting high angles can seem a little too ostentatious at times; but it never seems unmotivated. Even when verging into silliness, Branagh’s film is lousy with charm and feels largely cohesive from tone to visuals to story.

tThis tonal synthesis isn’t flawless. Your elderly relatives might find the film a little too frightening, your disaffected mates might rate it a tad too tame. But that’s the challenge of popular filmmaking. No matter how hard you try, you just can’t please everybody.

t

Verdict:

It’s ironic that traditionalist Branagh succeeds far better with genre hybridity than he ever did playing Poirot straight. Haunting is far from a perfect movie; but was anyone really expecting perfection from this famously uneven take on the famous sleuth? A Haunting in Venice muddies its proverbial waters and I’m reasonably grateful for that fact.

Rating: 6/10

A Haunting in Venice is in cinemas now.

Enjoyed this review? Check out these other reviews from Redbrick Film:

Review: Past Lives | Redbrick Film

Review: Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny | Redbrick Film

Comments