Culture Critic Georgia Henderson reviews Opera North’s latest rendition of Handel’s classic opera: Giulio Cesare

A golden performance (in more ways than one), the Opera North’s touring production of Giulio Cesare came to the Theatre Royal, Nottingham on 6th November with stunning scenery and a sparkling soprano. A re-run of the 2012 production, Tim Albery’s staging of Handel’s baroque masterpiece breathes fresh life into this tale of love, retaliation, and empire.

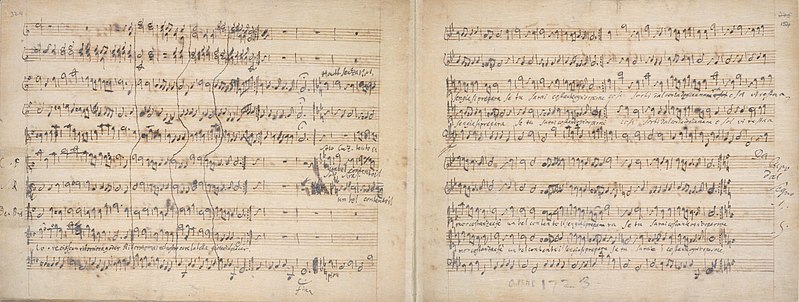

First performed in 1724, Handel’s Giulio Cesare in Egitto has enjoyed many successful adaptions since, including the famed run at Glyndebourne in 2005, and this production is certainly no exception. The libretto, by Nicola Francesco Haym, is based on the historical events of 45 BC and centred around the relationship between Caesar and Cleopatra, the power couple of two nations both in leadership contests. Following his victory in the Civil War against Pompey, Caesar arrives in Egypt amidst Cleopatra and Tolomo’s struggle for the Egyptian throne. Cleopatra seduces Caesar in order to bolster support for her campaign but ends up falling in love with the Roman emperor. Caesar, enchanted by Cleopatra’s beauty, is brought into the middle of the power struggle between siblings and the opera follows this complex tangle of alliances and revenge plots which culminates the crowning of a single ruler of Egypt.

“Caesar, enchanted by Cleopatra’s beauty, is brought into the middle of the power struggle between siblings

Albery’s production shrewdly maintains two-thirds of the original source (as it is hard to convince a modern audience to sit through four hours of Handel) and sets the characters in a modern yet indistinct time, pulling the audience into a world of deception and supremacy which remains relevant with its universal themes of war and passion. Manoj Kamp’s masterful handling of the score guides the Opera North’s orchestra skilfully through the ornamented music and layered melodies, though at times they did seem to overpower the singers on stage. Standing in for Christian Curnyn, Kamp’s conducting maintains great control especially given that this is his only appearance with the company in their touring production.

The most striking thing in this production is Leslie Travers’ glorious set. The central structure is the base of a pyramid that opens out onto slanted walls of mirrored gold that dazzles the audience with the opulence of an Egyptian palace. With cascading staircases and rotating pieces of gilded pyramid, the set moves to new angle with each aria. The visual spectacle matches the grandeur of the baroque music, and perfectly highlights the power struggle at the heart of this production. Surrounding the glistening gold pyramid, the stark concrete walls of the stage were stamped with SPQR. The contrast of the set reminds the audience of the opposing cultures of the republican Rome and dynastic Egypt.

“The visual spectacle matches the grandeur of the baroque music

The use of costume is particularly effective in this production. The bright blue silk pyjamas worn by Cleopatra and Tolomo are oddly regal and seductive, and their suits of gold armour in the battle scene dramatically casts them as equals in competition for the throne. But the most notable feature is the long gold fingernails which adorn Tolomo’s fingers while he is in power, almost witch-like and symbolic of his brutality. I would love to know why they chose this as the signifier of authority in this production, it has a very chilling effect. The opera concludes with the image of Cleopatra adorning these gold accessories, in her ‘crowning’ as queen of Egypt. This all stands in contrast to the dark, drab and conservative clothing of the Roman characters. Caesar is characterised by his muddied trench coat, and Sesto adopts the dress uniform of a modern soldier, while his mother Cordelia is dressed in a skirt suit. Political relationships are intertwined with familial and romantic connections in this opera, and the costumes help indicate the culture clashes that exaggerate these interactions. But all roads lead back to Cleopatra, in her slip dresses and heels, who demonstrates a level of power-play that the men are unable to compete with.

Bringing the Egyptian queen into the 21st century, a seductive Lucie Chartin masterfully commands the stage. Dressing and undressing, her continuous costume changes from silk robes, to embroidered dresses to satin hot pants, demonstrate a flirtatious female power unrivalled by any other character as she woos the leading men of Egypt and Rome. As Nireno sings, she is a woman who ‘gets what she wants’. No one can forget the image of the soprano singing ‘V’adoro pupille’ while bathing in a candle-lit pool on-stage. Chartin’s vocal performance is faultless and she presents the complex character of Cleopatra well through the exquisite control of seductive and vulnerable arias. She may use her beauty to seduce Cesare, but she is his match (maybe even superior) when it comes to power-play and the audience cannot help but root for Chartin’s Cleopatra.

“Chartin’s vocal performance is faultless and she presents the complex character of Cleopatra well through the exquisite control of seductive and vulnerable arias

Maria Sanner grapples well with the role of Caesar, adopting masculine aesthetics and particularly excelling in conveying the emotional side of the Roman emperor. Her chemistry with Chartin is believable and the pair work well together. However, there were times when the vocal performance lacked the gravitas expected for this titular role, in arias such as the challenging ‘Va tacito’, and did not quite match the magnitude of Cleopatra’s performance. The casting of Caesar is always a tricky decision, whether to go elect a countertenor or contralto, but Sanner’s mezzo-soprano tone is attractive and although she doesn’t quite pull off the masculine qualities desired, she still captures the audience and engages them throughout.

The small but talented cast of eight singers gave a credible performance however there were moments when Haymn’s lyrical feature was absent. The sometimes-shrill quality of countertenor James Laing, reprising his role as Tomolo, and the quiet arias of Catherine Hopper’s Cordelia drowned out by the orchestra lost the audience in moments. However, Heather Lowe’s strong vocal held the scenes between Sesto and Cornelia together. Despite the lapses in vocal quality, this did not by any means take away from the powerful performance demonstrated by all, and Albany’s product leaves its audience in a state of awe.

Albeny’s Giulio Cesare is a truly sensory experience in which all elements of the production have been crafted to convey the passion and power of Handel’s opera. While the singing is the central concern, credit must be given to the holistic excellence of the staging, truly reinforcing opera as the artform that combines arts greatest pleasures. The Opera North’s next production is Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro which will be coming to the West Midlands in March 2020.

Comments