Comment Writer Jonathan Korn gives an account of Irish history, placing it in context of current Brexit negotiations and explains why the backstop is so contentious

What the bloody hell is a backstop? And why the bloody hell do we need one?

These questions have dominated Parliamentary debate ever since Theresa May brought back her Brexit deal from Brussels. At the time of writing, 432 MP’s have resoundingly rejected the Prime Minister’s Withdrawal Agreement, and it is this wretched backstop which is the obstacle the PM has not been able to overcome.

Few expected the Irish question to be the main sticking point in negotiations, yet here we are, stuck in the quagmire of backstops, regulatory alignment and possible hard borders.

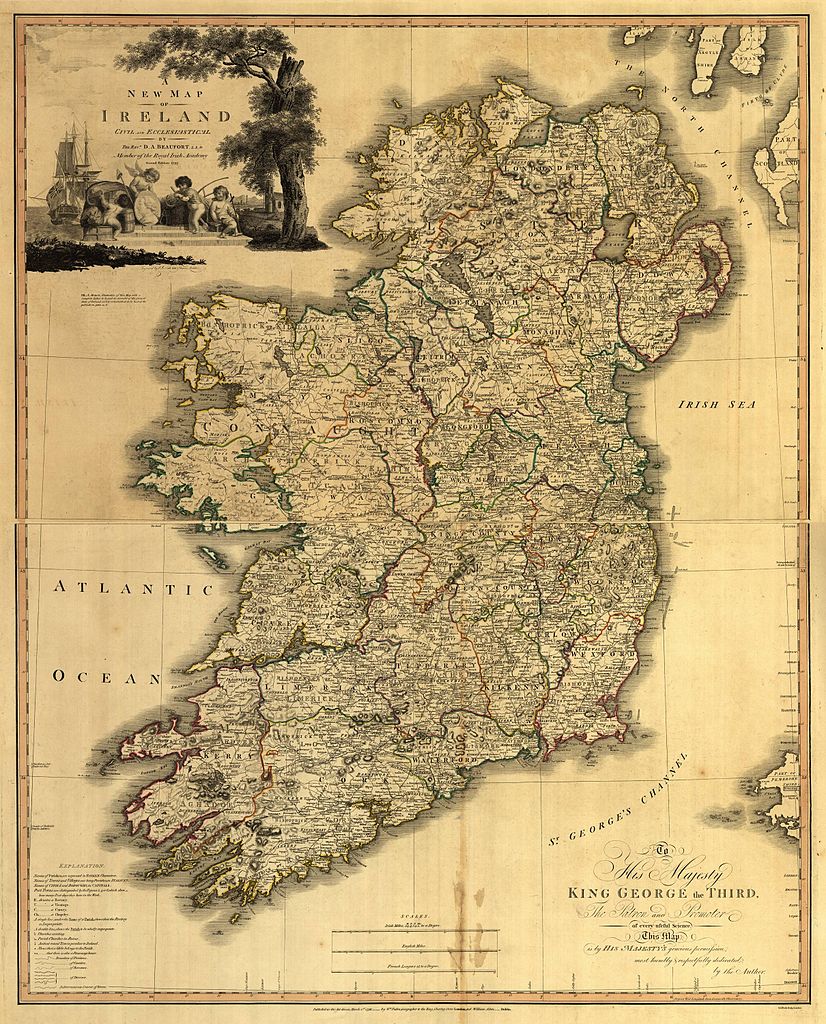

I think lots of people living in England think Ireland are just doing this to piss us off. Mini-revenge for colonialism, if you like. That Ireland are being deliberately difficult and holding up negotiations because they simply do not like us. And in fairness, they’d have every reason not to be big fans of the British. Under Elizabeth the First in the 16th century, a policy of subjugating the people of Ireland was pursued with a fury, with British “Plantations” set up and Unionists encouraged to settle there at the expense of the Irish farmers who owned the land. The Brits hardly got any nicer throughout the centuries. Irish Catholics were denied their political rights to representation in Parliament (until Daniel O’Connell’s campaign for Catholic Emancipation eventually found favour in 1829). The brutal suppression of the Easter Rising of 1916 and stories of British atrocities which emerged mark a dark chapter in our country’s history. In short, Leo Varadkar and the Irish government would have every reason to be obtrusive. However, this backstop is far more complex than a grievance blown out of proportion. It has historical roots and geographical significance, which the next few hundred words will try and explain.

stories of British atrocities which emerged mark a dark chapter in our country’s history

Ireland became a free state in 1922, yet didn’t gain full independence as a Republic from Britain until 1949. However, the Anglo-Irish treaty of 1921 saw the six Northernmost counties elect to remain in the United Kingdom. Since then, tension and hostility begot violence and bloodshed. The formation of the Provisional Irish Republican Army in 1969 and growth of Ulster Loyalist Paramilitary groups saw the simmering pot finally boil over, as Unionists and Republicans fought for the soul of Northern Ireland. 3,500 people were killed in the fighting that ensued, and for many citizens in the six counties, friends or even relatives were amongst the dead.

The Good Friday Agreement of 1998 finally brought an end to the Troubles. It allowed the citizens of Northern Ireland to decide their own destiny in a referendum which kept the country in the United Kingdom. It also ensured Republican and Catholic voices were not shut out of politics by introducing power-sharing government. Unionists and Republicans were forced to govern together to seek consensus rather than provoke further antagonism.

Yet the risk is that all could be lost. Power-sharing has collapsed, along with any semblance of trust between the main Unionist and Republican Parties (the DUP and Sinn Fein). A fragile peace is at breaking point, as Brexit looms and Ireland’s future remains unknown.

A fragile peace is at breaking point, as Brexit looms and Ireland’s future remains unknown

The root of the political problem is that Ireland (an EU member) will continue to share a border with Northern Ireland (a non-EU member) after Brexit. EU countries and non-EU countries have different trading rules and regulations, so when goods go from an EU country to a non-EU country or vice versa, the goods need to be checked to make sure they are in line with both countries’ regulations. If goods need to be checked, a checking point (also known as a border) is required.

Except no one wants a border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. The EU don’t want one, the Northern Irish don’t want one, the UK doesn’t want one. A hard border would, as all parties agree, sow the seeds of division just as the dream of unity seemed to have been fulfilled. Families with relatives on both sides of the border will be cut off from one another. A positive trading relationship between Ireland and Northern Ireland, so often the basis of good bilateral friendships, will become harder to maintain. And the bridges built by the Good Friday Agreement risk being torn down and replaced by walls.

Yet paradoxically, no one agrees on the means, despite agreeing on the ends. That’s where the backstop comes in. In order to avoid customs checks, the UK has pledged to align its trade rules with the EU by staying in the customs union so that frictionless trade can continue across the Irish border. In addition, the Withdrawal Agreement kept Northern Ireland in some parts of the Single European trading market, in order to make trade and movement across the border easier.

The problem is that MP’s hated it. The Democratic Unionist Party hated it because alignment with the Republic of Ireland is the last thing they want. Set up by Ian Paisley in 1971 at the height of the Troubles, the DUP is a party committed above all else to remaining part of Britain. Having experienced and withstood the bombing campaign of the IRA, an unwavering determination to resist Irish unification in any form is the DUP’s defining characteristic. Without understanding this historical hostility towards Republicanism, it is impossible to appreciate the ferocity of their opposition to the backstop. For the DUP, Northern Ireland being forced to basically stay in the Single Market (like the Republic of Ireland) whilst the rest of the UK leaves is anathema. As staunch Unionists who believe Northern Ireland should remain part of the UK, any deal which treats it even slightly differently they cannot support.

In short, we can only leave this arrangement if the EU says we can

The vast majority of MP’s hate the backstop for a different reason. Because it is a joint commitment to avoid a hard border, the backstop can only be ended with the consent of both sides. In short, we can only leave this arrangement if the EU says we can. It’s akin to being stuck in a lift with a mate who can refuse to open the doors for as long as he wants. For MP’s that supported Brexit to take back control of decision-making, a proposal which binds our hands in such a way was never going to hold much sway.

As a first-year history student, I am not yet cynical enough to believe humanity cannot learn from history. Understanding Irish history is absolutely essential to understanding British politics. And as the government seeks alternative solutions to the Irish question, it is vital to remember the Troubles and give everything to make sure their horrors are never repeated.

I understand the hostility to the backstop. It is hardly ideal. However, avoiding a hard border must be paramount. The citizens of Northern Ireland say so, the citizens of the Republic of Ireland say so, and history says so. If this means the backstop, MP’s should bite the bullet and put peace over perfection.

Comments