Gaming Writer Ellen Hill dives into Obsidian’s latest RPG, The Outer Worlds, to find out if space is truly free of capitalism but packed with fun times

I play what I like, and I like what I know – and that’s mainly the Fallout franchise. So to hear the developers of Fallout New Vegas were releasing what some have dubbed its sequel with similar gameplay but a whole new world to explore, I was ecstatic. Finally, I wouldn’t have to spend the first hour of so figuring out controls or gameplay mechanics (which is usually why I lose interest and revert back to my tried and tested favourites) but could completely focus on the story. Despite an overall resemblance to Fallout mechanics, there are also several changes – the skill and perk systems operate differently, as well as how you control companions. This leaves the game feeling pleasantly nostalgic without being mundanely recognisable – it’s not a regurgitation of Fallout: New Vegas but it’s retained all the best features.

“It’s not a regurgitation of Fallout: New Vegas but it’s retained all the best features

The Outer Worlds begins with a cutscene of infamous wanted scientist Phineas Welles docking an abandoned colony ship, Hope, to wake the player character from a 70-year cryosleep with the purpose of reviving all of Hope’s colonists to challenge the rule of capitalist corporation, Halcyon Holdings (more commonly known as The Board) that has overriding control of most of the solar system. You are then sent to the planet Terra 2, to the town of Edgewater, where you begin to discover more about the history and everyday life in the Halcyon solar system.

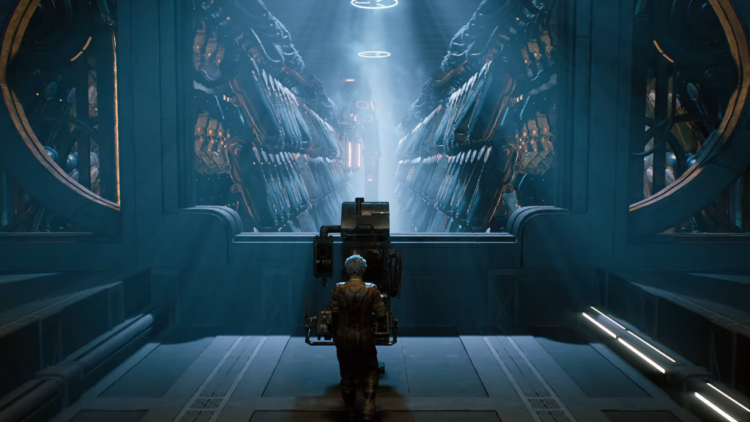

Over the course of the game, you travel around various planets, ships, moons, satellites, and asteroids, which each have their own unique story with quests to complete and characters to interact with. This creates the feeling of a huge, fleshed out world which you can immerse yourself in, losing hours trying to discover every detail in every conversation and terminal entry. Even the smallest features, like interactions between NPCs and your companions during dialogue independent of the player, or the personalised actions of crew aboard your ship, adds that something extra to the gameplay experience.

Although some of the quests can seem tedious, travelling back and forth to interact once with the same characters, the major quests in each area have depth and, in the final moments, present the player with a morally ambiguous choice. Usually in similar RPGs, like Fallout: New Vegas, there were obviously bad choices – eliminating the town of Goodsprings, encouraging cannibalism in the White Glove Society, pretty much anything that helps the Legion – but with The Outer Worlds, in areas like Edgewater and Monarch, I’ve struggled to predict which concluding decision is the ‘best’.

“There’s almost an unlimited number of possibilities

This unpredictability and variety of the outcome of quests, as well as the number of faction groups, and skill point and perk distribution, increase the replayability significantly. Want to play a charismatic bigwig that serves the corporation? How about a stealthy loner whose allegiance is only to themselves, and will take any job if the price is high enough? You can even go in with guns blazing, eliminating every NPC you meet, or do a complete pacifist run. There’s almost an unlimited number of possibilities, and you have the freedom to explore all of them.

During your initial character creation, similarly to the Fallout games, players choose their attributes, initial skill specialisation, as well as a career – a feature that will add a bonus characteristic (for example, the Team Mascot will receive +1 to inspiration skill). In addition to this, as you progress through the game, you’ll receive a pop-up informing the player of a Flaw your characters obtained – a penalty based on repeated experiences, such as receiving a particular type of damage or encountering a certain type of enemy. These are mainly optional, but they add another layer of depth and personality to your gameplay.

The Outer Worlds has four difficulty settings – story, normal, hard, and supernova – which can be altered during your playthrough, with the exception of supernova which can only be selected at the start. This is the most ‘realistic’ setting: your character will need to eat, drink, and sleep (but only in your ship) to survive. Flaws are mandatory and of course, combat is significantly more difficult. I began my playthrough on normal, and after completing the main quests in the Edgewater area (dying a remarkable number of times in the process), gameplay becomes a lot easier – levelling up skills and perks along with the acquisition of better weapons and armour with additional mods makes killing enemies notably easier. For me, this wasn’t an issue as my main focus is on the story and quests, but if challenging combat scenarios plays a bigger part in your enjoyment of the game, I would recommend upping the difficulty as you go on.

The story of The Outer Worlds takes you on a journey through a space Western imagination of late-stage interplanetary capitalism, filled with intense combat and morally ambiguous decision-making juxtaposed with humorous dialogue and interactions reminiscent of its stylistic predecessor, Fallout: New Vegas. These elements combine to create a challenging and enjoyable 40-hour experience, that can be replayed an infinite number of times. Is it perfect? No, but for me it comes pretty close.

Liked this article? Check out some other reviews here:

Comments