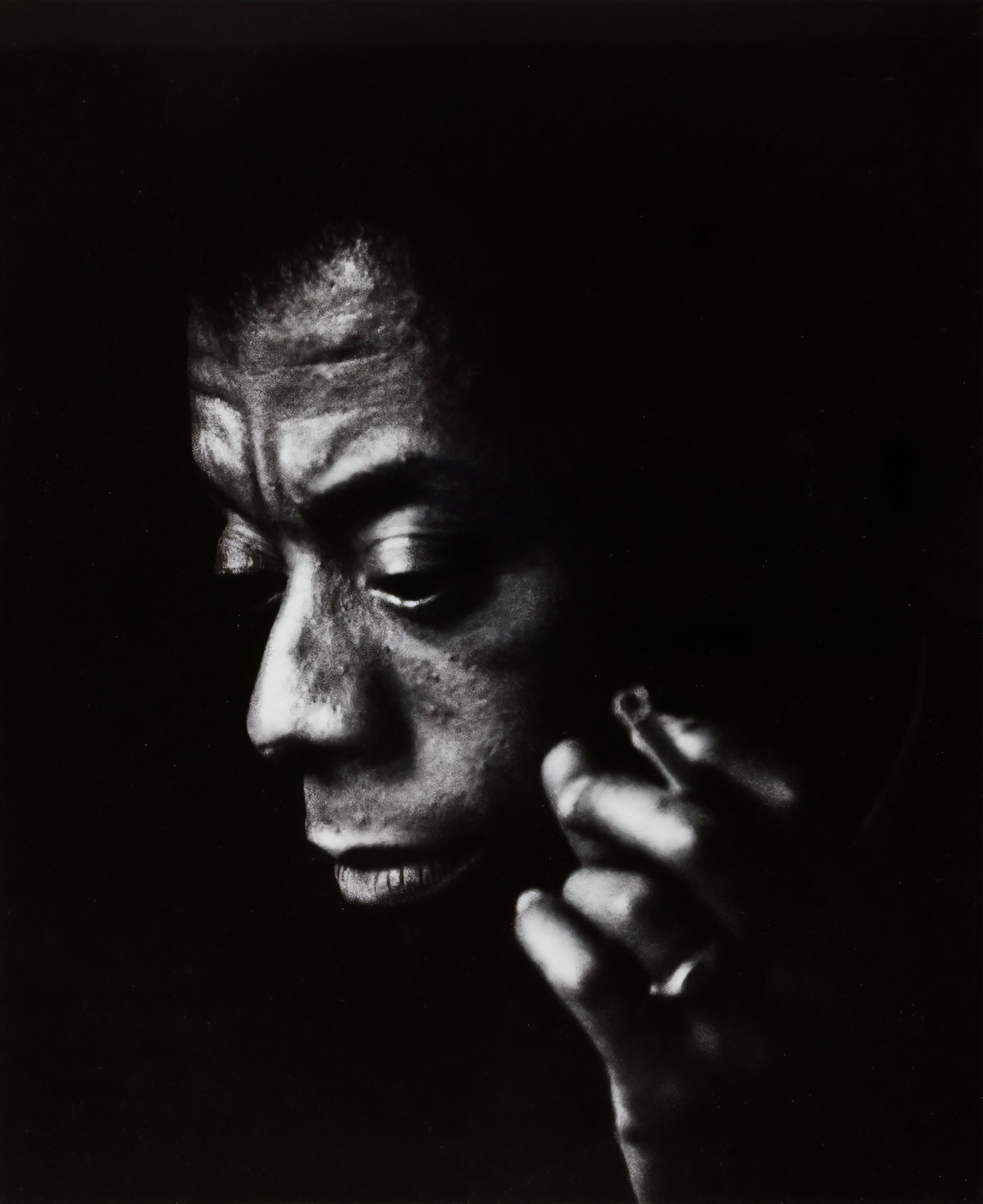

As part of Pride Month, Culture writer Leah Renz contributes to our Queer Biographies series by exploring the life and achievements of writer and activist James Baldwin

Race. Religion. Homosexuality. This thematic trinity is at the centre of all Baldwin’s work. Writing as a black man during the Civil Rights Movement in the US, and as a gay man during a time in which ‘gay’ was not even a term (Baldwin himself said he never considered himself ‘gay’; the only word he had was ‘homosexual’) perhaps it was inevitable that such themes would emerge. Reading his novels, and in particular his essays, the anger, passion, and pleas for understanding feel as important now as they were then, and maybe even more so.

Reading his novels, and in particular his essays, the anger, passion, and pleas for understanding feel as important now as they were then

Early Life

Born into the ghettos of Harlem, New York James Baldwin grew up the eldest of nine siblings and without ever knowing his biological father. He described Harlem as an area in which “poverty is piled high” and “Whole families [are] condemned forever to nothing… in the richest city in the world.” Amidst such despair, Baldwin found safety in the community of his local church, converting to Christianity at only 14 years old and preaching to crowds larger than those of his stepfather, also a preacher. Three years later however Baldwin lost his faith and became increasingly disdainful towards the church and religion, saying that “If the concept of God has any validity or any use, it can only be to make us larger, freer, and more loving. If God cannot do this, then it is time we got rid of Him.” Baldwin lost his faith

First Novel and the Role of Religion

His early upbringing in Christianity never left him however, and critics have remarked upon the cadences and rhythms of his writing as those of a biblical preacher. As a theme too, the church appeared time and again in Baldwin’s work, and his first novel Go Tell It on the Mountain is set over the course of a single day, following a boy just turned 14 and his family at church on a Sunday. The boy is a semi-autobiographical representation of Baldwin himself, and the story involves flashbacks to the character’s grandmother’s past as a slave (Baldwin’s grandmother was also a slave), and the boy’s fractious relationship with his father in a mirroring of Baldwin’s own difficult relationship to his stepfather.

Racism and the Move to Europe

After the death of his stepfather, Baldwin now aged 19 moved in with the modernist painter Beauford Delaney and spent the next few years of his life working odd manual labour jobs to support his family whilst becoming a self-taught writer, publishing essays and short stories, and at one time sharing a room with the then not-yet-famous Marlon Brando in 1944. Eventually however the racism he experienced became like a constant battle, so much so that “your world narrows to a red circle of rage”. Baldwin knew he had to escape the brutal racial segregation of the States; in his own words he felt that he “…was going to go to jail, I was going to kill somebody or be killed.” At 24, so broke he only had 40 dollars in his pocket, James Baldwin moved to Paris

At 24, so broke he only had 40 dollars in his pocket, James Baldwin moved to Paris, literary haunt of writers as renowned as Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Gertrude Stein. Paris exerted her magic over Baldwin also and the city becomes the setting for Baldwin’s second novel: Giovanni’s Room.

The Controversy of Baldwin’s Second Novel

Giovanni’s Room became the subject of controversy on two fronts: first, because it dealt with what contemporary Guardian reviewer David Walliams called the “abnormality” of homosexual relationships, and second, because it was populated entirely by white characters. Having been wrongly pigeonholed as a solely a writer of race relations in America, Baldwin’s American publishers feared that writing about white characters, let alone gay characters, would alienate his newfound readership. Their refusal to publish his work however did not prove to be an obstacle: Baldwin found sympathy amongst an English publisher, and the book which was once rejected has become a literary classic.

The book which was once rejected has become a literary classic

Civil Rights Activism

Many civil rights leaders, including Martin Luther King, did not want to be associated with a homosexual

Shortly after publishing this second novel Baldwin returned to the US and involved himself heavily in the Civil Rights Movement, befriending figures such as Malcolm X and Martin Luther King. As well as continuing to write and publish collections of essays, Baldwin made many public appearances in schools and in universities talking about racism in America. In 1965 Baldwin delivered his legendary ‘pin-drop’ speech at a Cambridge Union debate on the motion “Is the American Dream at the expense of the American Negro?” and in 1963 he appeared on the cover of TIME magazine, portrayed as a spokesperson for the Civil Rights movement. During the 1963 March on Washington however Baldwin was conspicuously absent from the list of speakers; many civil rights leaders including, Martin Luther King, did not want to be associated with a homosexual. As in the controversy surrounding Giovanni’s Room, some seemed to believe that his queerness fell into conflict with his blackness, perhaps in a mirror of the mingling shame and hope experienced in church as a teenager.

Legacy

James Baldwin was and is still, through his writing, a self-proclaimed “disturber of the peace”

One thing remains certain: James Baldwin was and is still, through his writing, a self-proclaimed “disturber of the peace”. His mantel has been taken up by the many writers he has befriended and personally inspired, such as Toni Morrison and Chinua Achebe, and Netflix’s 2016 visual essay I Am Not Your Negro is based on an unfinished final book by Baldwin. In summary Baldwin’s most important legacy is this: inspiring writers and readers to continue to challenge a world still filled with injustice.

Read more Queer Biographies of inspiring figures:

Queer Biographies: Keith Haring

Queer Biographies: Gertrude Stein

Queer Biographies: Robert Mapplethorpe

Comments