Film Critic Tom Green finds that Noah Baumbach’s adaptation of Don DeLillo’s White Noise succeeds and fails due to its fidelity to the novel

Baumbach’s adaptation of White Noise could hardly have landed on screen at a more opportune moment. The source: DeLillo’s portrait of an America beset by modern pathologies, relentless stimuli, a malfunction and distortion of collective memory, and existential anxieties amid catastrophe. Uncanny – just replace ‘toxic airborne event’ with your modern crisis of choice.

Baumbach’s fidelity to the novel is both an asset and a burden

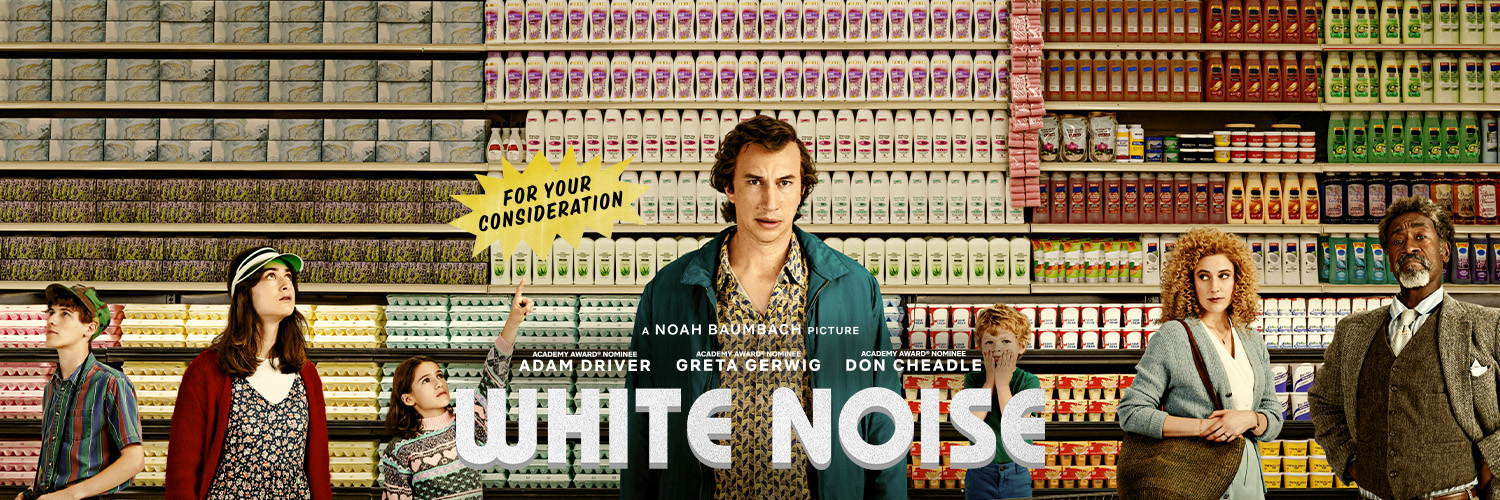

White Noise (2022) sees Jack and Babette Gladney (Adam Driver and Greta Gerwig) in a cushy Ohio suburban life. Jack is a tenured professor of Hitler studies at the local university and grapples with an intense fear of death. Part satire, part disaster movie, part meditation on modernity, White Noise laudably wrangles with DeLillo’s prose. Baumbach’s fidelity to the novel is both an asset and a burden, rarely has Netflix funded a genuinely risky vision like this although judging by the lack of enthusiasm for the film they’re unlikely to again.

The disorienting, skittering, stimulating screenplay reaches great heights, particularly in the second act as Jack listlessly wanders through survival shelters, assaulted by speeches from wannabe modern messiahs, conspiracy theories, static buzz, nagging questions, and a brush with death. Driver plays Gladney brilliantly, managing to bring a surprising tact to the aging academic, stalking and hunched over, making grand gestures in his unsettling lectures.

Unfortunately, the purity of adaptation sometimes frustrates. There are moments in White Noise when the screenplay becomes jarring, which confirms a personal suspicion that DeLillo’s idiosyncratic approach to dialogue doesn’t work well in real-time; it’s hard to imagine any of the pinballing language games in the first act of the film occurring over breakfast. It’s difficult to decide whether the mad barrages of phrases and questions in the Gladney kitchen are bang-on, or just indicative of DeLillo’s overbearing obsession with language philosophy.

So central to White Noise (the novel) is the idea that language constructs a reality that a screen adaptation may have been doomed from the beginning. Regardless, it reminds us that the volume of superfluous information we receive, distilled down into soundbites and clips dislocates us from the flow of everyday life.

Baumbach retains DeLillo’s laser-focus on the family, described as ‘the cradle of misinformation’. Where better to examine the fear of death than the unit by which much of life is mediated? There are fascinating (albeit occasionally unbelievable) conversations between members of the Gladney family, who are often turned against each other in service of bad habits and secret rendezvous. Baumbach has not lost touch with his sentimental side and carries his ability to direct family dramas from Marriage Story (2019) over to this effort.

The film is also visually exquisite and manages to replicate DeLillo’s suburban landscape with remarkable tact. There’s the pastel-washed suburban Blacksmith, the dingy neon-splashed interiors of SIMUVAC bunkers, and rain-soaked, fire-spewing industrial Irony City, each providing a suitable reflection of the character’s mindscapes. Some of the set-pieces are inspired too, the splicing of Jack’s lecture on death with a train careering towards chemical tanks is an adept use of the medium.

[The film] contains elements of slapstick and Spielbergian blockbuster banalities that don’t gel with the source material’s message

Unfortunately, Baumbach falters on the tone of White Noise, which is markedly more jovial than the novel. While the source is considered satirical and often provokes laughter, there’s cynical pathos behind DeLillo’s prose. The film, on the other hand, contains elements of slapstick and Spielbergian blockbuster banalities that don’t gel with the source material’s message. Also bizarre is the LCD Soundsystem musical number at the end, accompanied by choreography from supermarket workers and cast members. Commentary on the interplay between culture and consumerism or misjudged marketing gimmick? Either way, it falls flat.

Ultimately, it’s doubtful whether a ‘pure’ DeLillo adaptation would work on screen. His work tends to rely on the novel form, and there has yet to be a successful translation to film. David Cronenberg gave Cosmopolis a try, as did Benoît Jacquot with The Body Artist titled Never Ever (2016). Perhaps a better approach to DeLillo would be to keep the core thesis but innovate the form for cinema. Regardless, Baumbach’s attempt is admirable, most notably for the huge risk he took by pursuing a fairly niche passion project.

Verdict:

White Noise both soars and crashes because of its loyalty to DeLillo’s novel. While formally brilliant, the faithful screenplay falters. Baumbach misses the mark tonally, creating a disjointed and alienating atmosphere, which could be clever meta-commentary but fails to impress regardless. After its catastrophic financial performance, we’re not likely to see a director take a commendable risk like this anytime soon, flaws and all.

Rating: 3/5

White Noise is now streaming on Netflix.

Enjoyed this article? Check out these other ones from Redbrick Film:

Review: Matilda the Musical | Redbrick Film

Comments