Film Critic Charley Davies takes a deep dive into Emerald Fennell’s Promising Young Woman, showing how heavy topics like sexism and sexual assault can be portrayed within cinema

Content Warning: This article contains discussion of sexual assault, violence against women, and suicide, as well as major spoilers for the film Promising Young Woman

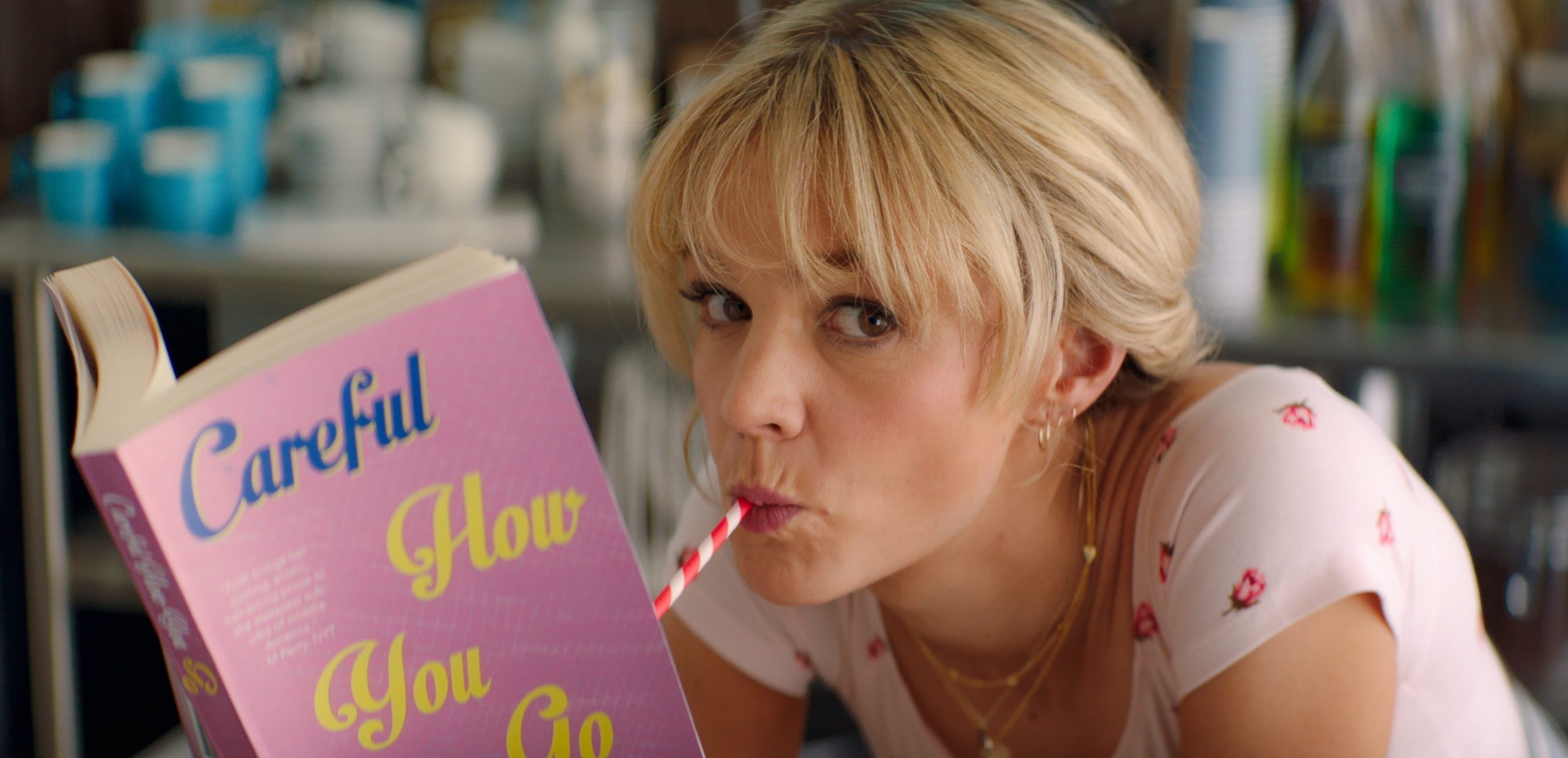

Though dressed as a mainstream, popcorn flick, Emerald Fennell’s directorial debut Promising Young Woman (2020) holds feminist morality at its core. From the offset, 30 year-old med drop out Cassandra “Cassie” Thomas (Carey Mulligan) is just another Britney wannabe, introduced with “hair plastered to her face, mascara under her glazed eyes, the skirt of her pinstriped work suit riding up”, as stated in Fennell’s screenplay. It is only when multiple ‘nice guys’ take Cassie back to their apartment, to liquor and feel her up, that the audience can understand Cassie’s true game: to passively accept these men’s advances, until she reveals herself to be stone-cold sober and take revenge against those only seconds away from violating her. Though such behaviour becomes habitual for Cassie, the film becomes a plea for women to take back the night in the face of everyday sexism.

we see Cassie’s motivation to ‘right’ the ‘wrongs’ of each accomplice maintaining the same evasiveness

Fennell nods to all that is wrong in our sexist world by upholding the attitudes which limit women’s right to exist freely. To many men in Promising Young Woman, a woman who has let herself go physically means a woman who is, in the words of victim Paul, “asking for it”, and is susceptible to “entirely one-sided” physical attention, as is the description of the encounter between Cassie and Jerry. While this language is familiar and accepted by people in and outside of the film, what this film goes on to showcase is how attitudes towards sexual assault cannot be avoided when this affects someone you know. When it is revealed that Cassie’s former classmate Al Monroe (Chris Lowell) raped her best friend Nina a decade prior, we see Cassie’s motivation to ‘right’ the ‘wrongs’ of each accomplice maintaining the same evasiveness towards this sexual assault: to former classmate Madison McPhee (Alison Brie), who had undermined Nina’s subsequent allegations as “crying wolf”, Cassie hires a man to take to a hotel room; to the medical school dean (Connie Britton) choosing to protect the futures of Al and his friends, she pretends the dean’s daughter had been taken to the same dorm room Nina had been assaulted in; and she harasses the lawyer who had harassed Nina into dropping her charges against Al.

From these moments of defiance, the illusion is created that sexism is a battle which Cassie is winning. Indeed, the hotdog she devours in front of catcalling builders the morning after she frightens Jerry and after the title credit appears could be read as a castration symbol. But as much as Promising Young Woman indulges in flickers of feminist girl-power and glitzy hits like Juice Newton’s ’Don’t Call Me Angel’, Britney Spears’ ‘Toxic’ and Paris Hilton’s ‘If Stars Were Blind’, these comedic elements sink into a black hole against Cassie’s turbulent emotional journey that is fuelled by sexism. Juxtaposed against Cassie’s parents’ pastel-pink dream of a living room, Cassie watches a recording of Nina’s assault using the ten-year-old mobile Madison had dropped off. The thriller nature becomes exacerbated when we hear the voice of Ryan (Bo Burnham), Cassie’s new boyfriend and former med school classmate, on the recording and him failing to intervene. At this, stomachs drop. Though we understand #NotAllMen commit sexual assault, the people we truly invest in as the ‘nice guys’ can disappoint us by as passive bystanders.

Cassie chooses an undefined quest for justice in respect to her late best friend over any men in her life

The action of the film becomes a criticism of women being forced to adapt against men who continually get away with traumatising them. Nina is revealed to have killed herself, Cassie drops out of medical school, yet even ten years on, Ryan would not own up to Cassie’s true whereabouts when she becomes a missing person, to presumably avoid being indicted for Nina’s assault. What is fundamentally unfair is how Cassie is not afforded the same privilege; her preoccupation with the past and justice for Nina is what leads to her demise. To be smothered to death by the same person who raped her best friend is the ultimate tragedy. In her interview with Variety, Fennell justifies the “unrelenting” nature of Cassie’s one-shot death sequence, filmed within one two-a-half-minute long shot, as being necessary for avoiding the trope where a woman is the one to triumph, and might even up with a man at the end. Instead, Cassie chooses an undefined quest for justice in respect to her late best friend over any men in her life. Ryan just becomes a means to an end when Cassie blackmails him into giving her Al’s party address to avoid having Nina’s recording leaked. The film becomes a tragedy for the women who fight back and cannot survive against a patriarchy who feel entitled to women’s bodies.

To me, Promising Young Woman had such a successful award season, winning the Best Original Screenplay at the 93rd Academy Awards, and a nomination for Mulligan for Best Actress, because it is both a digestible and undigestible reflection of a world we recognise as our own. Even on the day I write this, I experienced multiple men looking me up or blurting out something at me in public spaces; and on a more serious note, UoB students were reminded on the night of the 17th March 2021 vigil, that 97% women have had experienced some form of sexual assault.

This is why I am glad that feminism pervades the off-set world of Promising Young Woman, too. A film written and directed by the show runner of the second series of female-led Killing Eve and also the portrayer of Camilla Parker-Bowles in the fourth series of The Crown, I garnered only a promising expectation of the film which would be snapped up by Margot Robbie’s production company, LuckyChap. I am glad that characters like Cassie were able to be brought to life by wonderful actors like Mulligan, shedding light on the power women can hold, but how their power is limited if the men in their lives do not enact change, too.

For more reflections on cinema, have a look at these Redbrick Film articles:

Rebrick Rewind: Legally Blonde Turns 20

Comments